Mango. Our favorite fruit here at home. Whenever we talk about moving to another country, my younger daughter, Alex, never forgets to remind us her two conditions. First, we have to bring her dog. Second, we cannot move anywhere where coconuts, bananas and mangoes do not grow. That’s how much she loves mangoes. So do the rest of us in the family.

Where did mango originate?

India, according to known documented accounts. They reached the Philippines in the 15th century and Brazil in the 16th century. Today, they are grown in just about every part of the world where there are frost-free winters, including Africa, Australia, the Caribbean, Hawaii, central America and even in the Andalusia region of Spain.

Mango cultivation is serious business in the Philippines

Mangoes grown and harvested in the country are exported globally and they are world famous. Just to show you how seriously mango-growing is in this country…

Years ago, on a road trip, we passed by a mango orchard where the fruits growing in trees were enclosed in paper bags. I learned later that the bags protect the fruits from insects, birds and damage during harvest.

Can you imagine how labor-intensive it is to bag the mangoes one by one? But it is done anyway because Philippine mangoes command a good price in the global market.

And, as another illustration of how important mango is to the Philippines, in 2005, there was some brouhaha when the Philippine government discovered that Mexico was exporting its mangoes under the name “Manila mango” ostesibly because the first mango seedlings that grew in Mexico came from the Philippines via the Manila galleon trade. In 2015, the Philippines and Mexico signed an expanded intellectual-property (IP) cooperation agreement but, as of 2017, Mexico was still exporting their homegrown “Manila mango” to the United States.

Mangoes vary in size, shape, eating quality and skin color

Just because mangoes grow in so many parts of the world doesn’t mean all mangoes are equal. There are hundreds of mango cultivars. The flesh of some are watery while others have a custard-like quality. Lucky for us, the flesh of the mangoes from the tree in our garden have custard-like flesh.

Some mangoes are small and round, others are oval, and there are the ones shaped like a kidney.

The skin of tropical mangoes are green when unripe and yellow when ripe. Subtropical mangoes have reddish skin.

But whatever the size, shape, eating quality and skin color, mangoes share one characteristic — they all have a single seed, also referred to as stone or pit, that grows between the fleshy mesocarp that we like to call “cheeks”. This seed which does not easily separate from the flesh is found right at the center of the fruit. In the case of kidney-shaped mangoes, the shape of the stone follows the shape of the fruit — thinnest at the bottom and thickest at the center.

How are mangoes consumed?

In Asia, mangoes are eaten raw or cooked. Both unripe and and ripe mangoes are consumed extensively in various ways. A few recipes (Asian and non-Asian) that include mango among the ingredients.

How to cut and skin ripe mango

The flesh of ripe mango is sweet, soft and slippery. To get the most of its luscious flesh, start cutting from the top near where the fruit stalk was before the fruit was plucked from the tree. You can’t miss it because it’s a dark spot right on top of the mango.

Cut the “cheek” from top to bottom letting the knife slide as close to the bone as you can manage. Repeat with the other side.

Because the flesh of ripe mango is soft, you can easily scoop it to separate it from the skin. I just use a spoon; other recommend a drinking glass to scoop out the flesh in one perfect piece. Optionally, you may want to score the flesh, in whatever shape you like, before scooping it out.

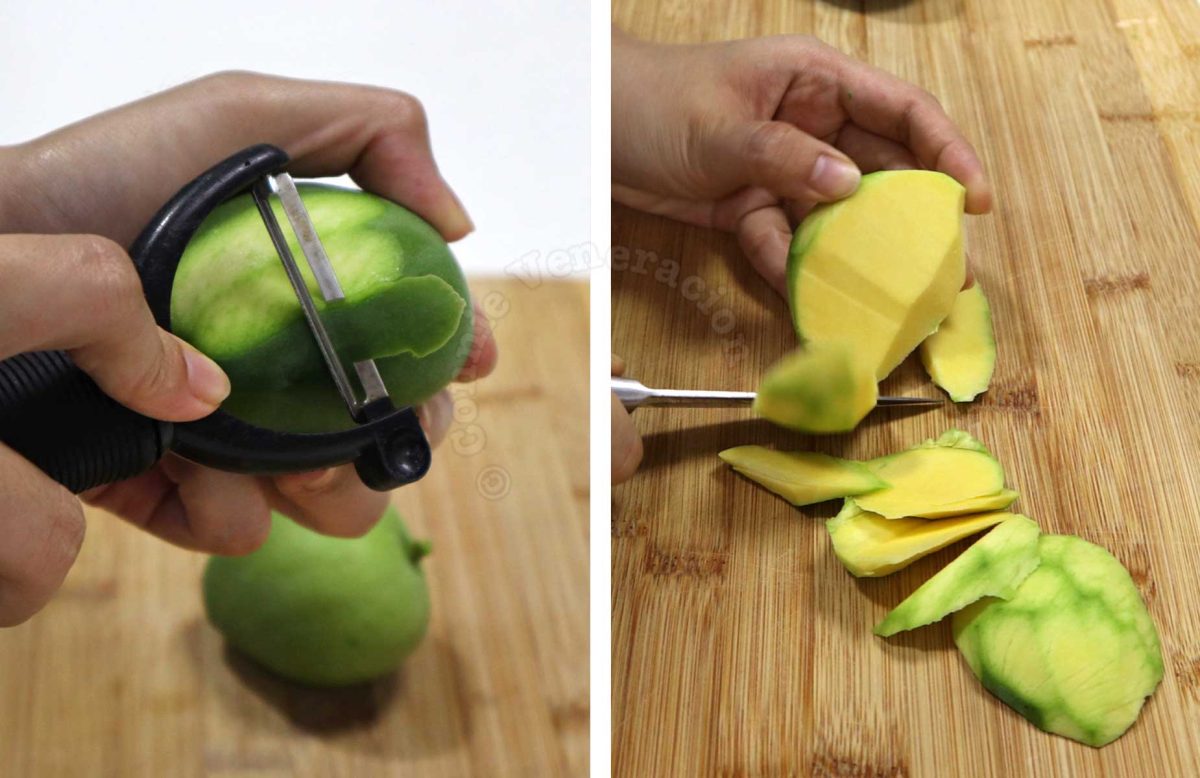

How to peel and cut unripe mango

Unripe mangoes require a different technique.

Because the flesh of unripe mango is more crisp than soft, you cannot simply cut off the two “cheeks” and scoop out the flesh.

What we do at home is to use a vegetable peeler to remove the skin first. A paring knife will do the trick too but there is a tendency to pare too deeply so that chunks of flesh get cut off along with the skin. What a waste, really. So, we prefer a vegetable peeler. With the skin discarded, we cut around the stone at the center to get as much flesh as we possibly can.