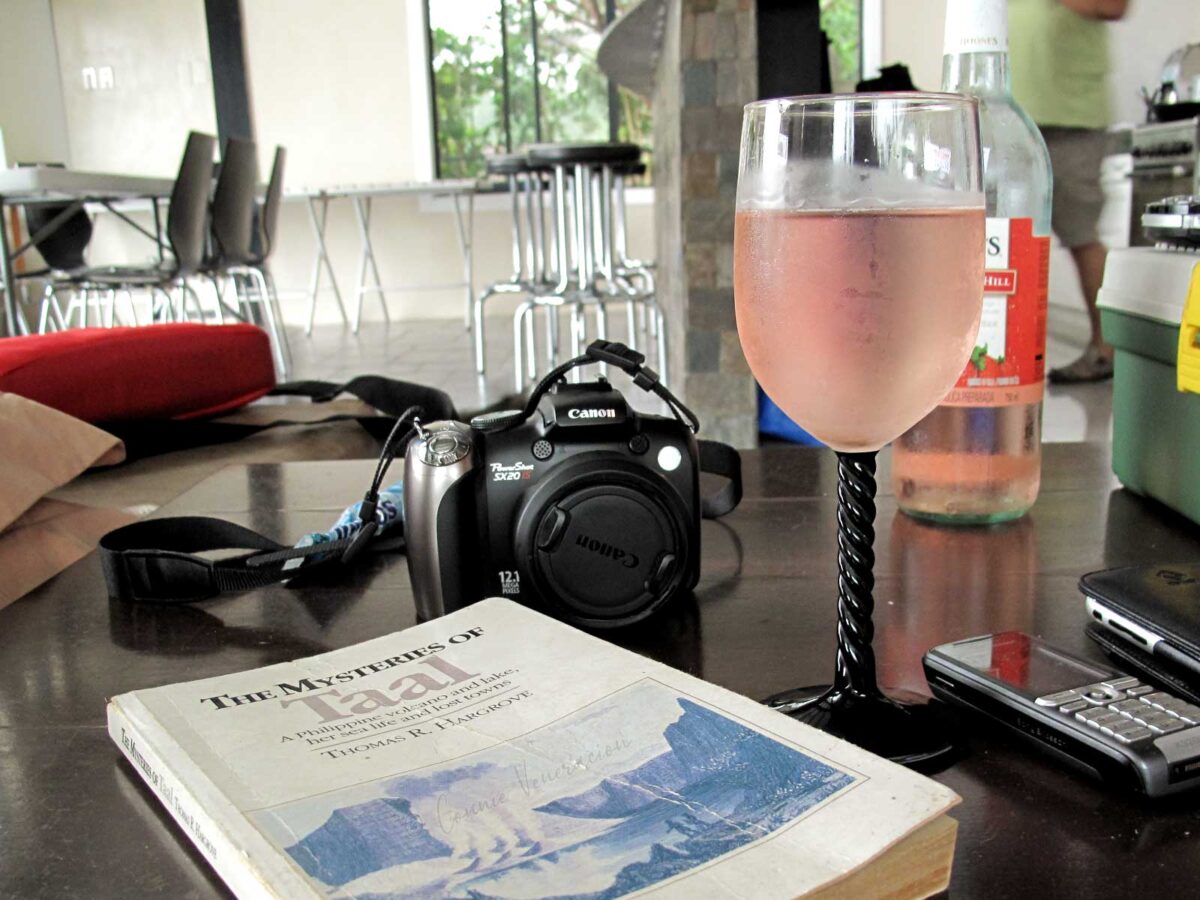

The fish is Sardinella tawilis, the lake and volcano are both called Taal, and the book is The Mysteries of Taal: A Philippine Volcano and Lake, Her Sea Life and Lost Towns by Thomas Hargrove.

I discovered the book over twenty years ago but I had been eating tawilis long before that. My fascination with Taal goes back to my childhood. But it was something more recent that triggered memories of the volcano in the lake.

It was a dinner party. It’s been four years since the pandemic hit, and we finally resumed our annual post-Thanksgiving-pre-Christmas dinner with cousins from my mother’s side of the family. As usual, it was a potluck affair. There was a whole lechon, roast turkey with all the sides, callos, fresh spring rolls and fried tawilis.

Curiously and amusingly enough, the dinner party was hosted by the former owners of the house where I first read Thomas Hargrove’s book. The seed of this story germinated on the ride home from dinner.

Among the city folk of Metro Manila, a popular weekend activity is to drive to Tagaytay City. Perched on a ridge over 30 kilometers long and with an average elevation of 600 meters above sea level, the climate is comfortably cool. A welcome respite from the soaring temperatures in the city which can truly get offesive in the summer.

The weekend activity slowly grew into a local tourism industry. Over the decades, the bamboo-and-nipa picnic huts that could be rented by the hour were slowly replaced big businesses. Today, the ridge is lined with hotels and restaurants that, aside from accommodations and food, offer the city’s most famous attraction: a view of Taal volcano and the lake surrounding it.

It’s quite a sight — the volcano in the lake. There was a park nearby where you could just spread a blanket, take out whatever was in your picnic basket and just enjoy the food and drinks in the cool weather while gazing at the magnificent view. Or you could rent one of the countless picnic huts interspersed between the swankier establishments.

We went there often as a family when I was a young girl. My then-boyfriend-now-husband and I used to picnic there when we were dating. He and I have brought our daughters there more times than I can count — sometimes on day trips but, more often, for a night or longer. We discovered something new on each visit — a new cafe, a restaurant that served better bulalo or crispier tawilis, plant stalls that sold hard-to-find herb seedlings…

The lake and volcano, however, are not part of Tagaytay City which is part of the province of Cavite. Taal lake and volcano are in the province of Batangas, but not in the Municipality of Taal. The northern half of the volcano island is part of the Municipality of Talisay while the southern half is in the Municipality of San Nicolas. The lake surrounding it is part of a few more municipalities and two cities.

Why then are they named Taal? The answer to that is in the book that I found in a house overlooking the lake and volcano.

The book by Thomas Hargrove

Around 2002 or 2003, a cousin-in-law and his family built a house on their long vacant property in Tagaytay. Soon, there was an invitation to spend the weekend there. And it was on our first visit to the house that I discovered Thomas Hargrove’s book. It was just after breakfast and I brought down my second cup of coffee to the lower level of the house. With everyone chit-chatting upstairs and the children busy with whatever form of entertainment they managed to devise, I had the entire lower level to myself.

Sipping coffee while gazing at the volcano sounded like a lovely way to spend the next half hour or so. But, as mysterious and as legendary the sight might be, my eyes got tired after a while. I looked at my coffee cup — already empty — and wondered if I should rejoin the others upstairs. I got up, I collected my coffee cup and started walking toward the stairs. I passed by a small low table near a wall and saw the book. The Mysteries of Taal: A Philippine Volcano and Lake, Her Sea Life and Lost Towns by Thomas Hargrove. I rejoined the others two to three hours later after I had finished more than half of the book.

I had never heard of Thomas Hargrove. I’m not even fond of non-fiction books. But I enjoyed that book so much that, on the same night we got home, I tried to find out more about him. I already knew he was connected with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) because his short bio on the book jacket said so. Then, I read that after his stint with IRRI, he worked in Colombia where he was kidnapped and held for 11 months by guerillas. He kept a diary of the ordeal and later published it into a book. That book became the inspiration behind the film Proof of Life that starred Russell Crowe (but it was David Morse who played the role of the kidnap victim).

I wrote about all of it and published it in an old blog. About finding and reading the book, searching for more information about the author and discovering the connection with Proof of Life.

A week or two later, there was an e-mail from Thomas Hargrove who was apparently Googling his name (or his book or Taal) and found my blog. We e-mailed back and forth a few times talking about bulalo mostly. Thomas Hargrove died in 2011. Three years later, I found his book in the same house where I first read it. And I read it again.

Why is the book so important in this story? Because it holds the answer to:

- Why the lake and volcano island are named after an old town to which they do not belong and

- How tawilis, a species of Sardinella (a genus of saltwater fish), could possibly exist in fresh water

The book is out of print but there exists a video (parts one and two) of an episode of an old TV show broadcast before the publication of the book where Thomas Hargrove talked about the well-documented eruption of Taal Volcano in 1754. Among the things he noted:

- Towns were buried in the lake and the location of the towns that survived changed. While the town of Taal used to be on the southern shore of the lake, today, it is farther south.

- Marine life in Taal Lake is curiously teeming with characteristics of saltwater life. Coral has been found there. There were sharks until hunters wiped them out in the 1930s. There were poisonous sea snakes. And then, there’s tawilis, a sardine — and sardines are saltwater fish.

Taal

So, Taal actually moved? Yes. But not the lake nor the volcano.

It’s not anything as dramatic as land that rose after the 1754 eruption and the town of Taal was literally pushed southward as new land separated it from the southern shore of the lake. It’s nothing like that.

Taal was founded by Augustinian friars in the 1500s. The town was originally larger. Think of it this way: Had anyone asked where the lake and volcano were located, there would have been no answer more logical and obvious than “Taal.” That was how large it used to be.

By 1732, Taal was the capital of Batangas and, therefore, the seat of provincial power. Since it was the friars that were wielding power, the exact location of Taal was effectively where the friars were. When the volcano erupted in 1754, Taal was actually located where San Nicolas is today. But the friars felt it was too dangerous to stay, so they moved southward, along with the capital, and farther away from the lake and volcano.

The boundaries of Taal have been redrawn so many times to give way to the creation of new towns. In 1955 and 1961, the municipalities of San Nicolas and Santa Teresita were created by law, respectively, and what remained of Taal was physically cut off from any portion of the shore of the lake.

Meanwhile, the lake and the volcano never acquired new names. They remained, and still remain, Taal Lake and Taal Volcano.

Tawilis

How did a sardine become a freshwater fish? Volcanic eruptions and evolution. Thomas Hargrove talked about documentation of evidence that the lake was once connected to the sea by a wide channel. Constant volcanic eruptions made that channel narrower and narrower, until it was finally closed leaving behind saltwater marine animals. With the connection to the sea cut off, the sealed off lake eventually turned purely freshwater. To survive the less saline environment, these marine animals, including tawilis, adapted and evolved.

Imagine that. The perseverance to survive. Yet, today, tawilis has been declared an endangered species. Overfishing. Decades of overfishing in the lake. You see, as the local tourism of Tagaytay and nearby towns of Batangas blossomed, the demand for bulalo soup and fried tawilis grew. They became tourist attractions too alongside the magnificent view of the lake and volcano.

What’s so special about tawilis anyway that people actually seek it when they order a meal in Tagaytay? The only way I’ve eaten it is fried. It’s meaty, the bones and scales are so soft, it has no strong fishy smell and its size really makes it an ideal finger food. That’s probably why it is traditionally served deep fried and crispy — the perfect beer companion.

Tawilis is a sardine and, as such, there really isn’t anything extraordinary about it except that it is the only sardine to exist in fresh water. But most consumers don’t really care about that. It is the association with the lake, the fact that it is harvested in only one lake, and how there’s limited supply and a high demand, that makes it attractive. I wonder how many people who have ordered tawilis know its story.

Tawilis is not easy to source in Metro Manila. And it is not uncommon to find restaurants that pass off a different fish as tawilis. So long as the size, shape and general apprearance are similar, how will unsuspecting consumers know?